When I was in high school, my track coach showed me a picture of her wedding. I’m sure she was a beautiful bride, but all I remember about the image was the prominence of her watch tan. A runner herself, she laughed about the fact that the ghost of her watch, a pale bracelet of skin around her wrist, was memorialized in every wedding photo.

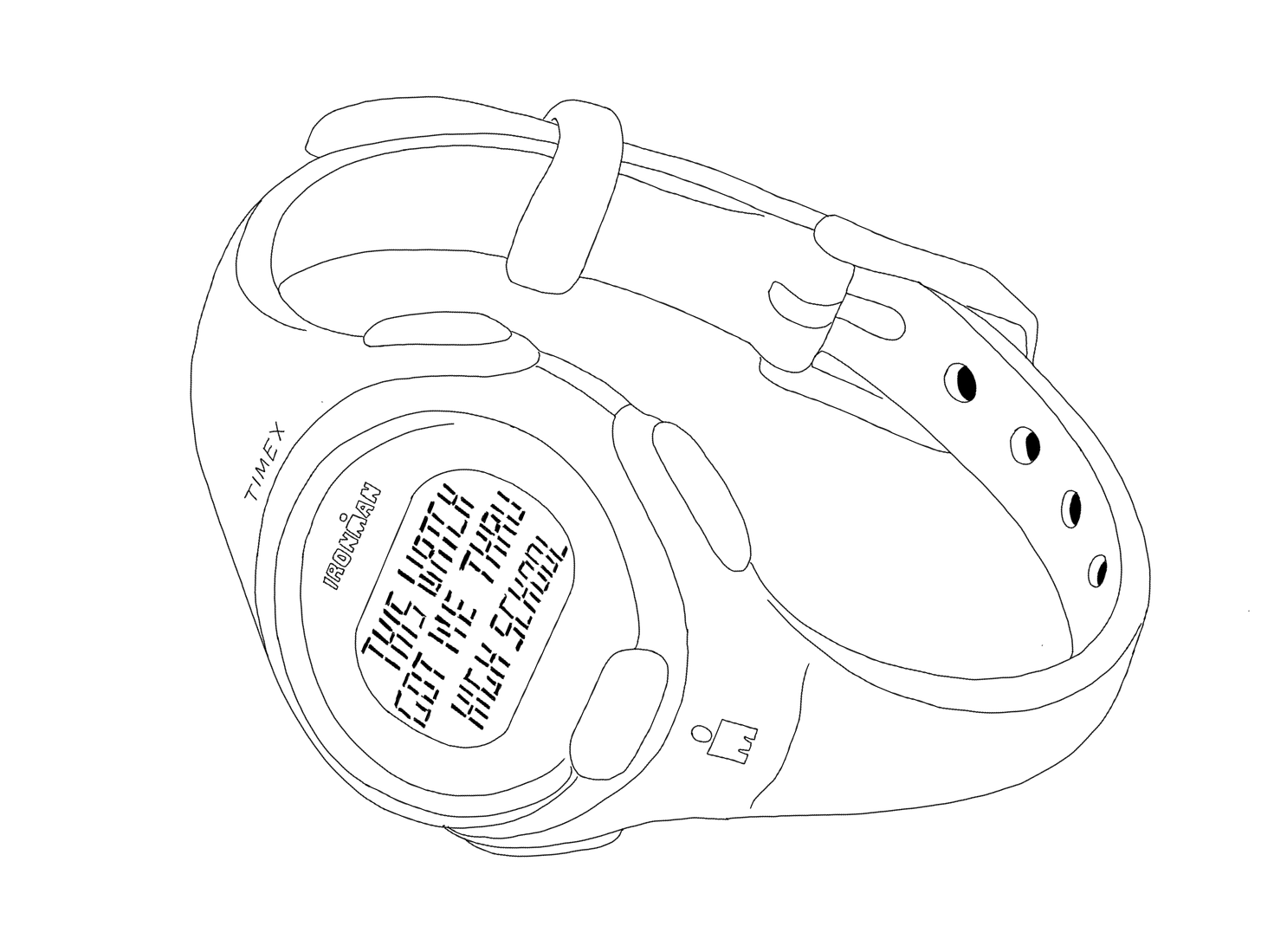

By the time I saw that picture in high school, I had already been working on a watch tan of my own. Back when I first joined my middle school’s cross country team, my mom bought me a slim light blue TIMEX watch from Target. I had never worn a watch before, but once I did, I couldn’t imagine taking it off. I timed everything: how long my runs were, naturally, but also the length of my mom’s errands, the presentation of a particularly long-winded classmate, Sunday sermons.

I set my watch to “school time,” several minutes behind the exact time of day, so that I would know exactly when the bells would ring. Classmates would ask me how much time we had left in that period, and I would be able to tell them precisely, down to the second, counting down until the bell rang, seemingly on my command. It was a power no one else in the school possessed, because no one else was willing to calibrate her life to the inaccuracy of the Tri-North Middle School bell schedule.

My watch became a part of my body. I wore it in the shower. I wore it to sleep. Of course, I wore it for every run, and while the rest of my body bronzed in the Indiana sun, the band of skin beneath my watch remained deathly pale. I was proud of it. It signaled my commitment to my sport, the time and miles I’d put in. And it also signaled my identity as a runner: the watch itself was evidence on its own, but in its rare absences, the silhouette on my skin suggested that something was missing. I’d absorbed the watch into my sense of self.

It was a machine that amplified my innate tendencies. I was exacting, and the watch was an instrument of precision. I liked to know things, and with a watch, the time of day belonged to me. The watch lent a sense of power—knowing the time was as close as I could get to controlling the time.

I felt this most strongly in the context of running: it made intuitive sense that if I wanted to run faster, I had to know exactly how fast I was already running. I timed and kept meticulous records of my training. I memorized the PRs of the top girls across the state, and every Monday, after the weekend’s races, I would log on to Indiana Runner, a bare-bones website that hosted race results from across the state, and study the new fastest times my competitors had posted.

My senior year of college, I got my first GPS watch. It was lime green with a bulky square face. And it added yet more ways to quantify my runs and my life: I knew distance and pace; I tracked sleep and steps; I could upload the data to apps like Strava, the social media of the running and biking worlds where other people could see your routes and races and weekly mileage. Strava captured my fitness over time and displayed leaderboards for different running segments and loops, constantly in flux as people one-upped each other. It was all, of course, made possible by my watch.

Also made possible by my watch was the accompanying anxiety about time. It showed up, shows up, in every dimension of my life. I am always in a rush, even when I don’t need to be. I’m racing out the door, threading my belt while jogging to catch a bus, then arriving at my destination early and waiting 20 minutes for everyone else to show up. I am stressed about how long it will take to get to the next place, if I’ve scheduled myself enough time, if I’ve scheduled myself too much time. I’m thinking several steps ahead, not just, “Am I having fun now?” but “At what precise moment would I need to leave to catch the last BART train?”

It’s there in running, too. I’m anxious when I’m running slower than I used to, worried often that I’ll never take another stab at my Big Running Goals, that I’m wasting my years as a late 20-something, the prime of my abilities as a runner, my clock running out to accomplish the things I’ve long dreamed of doing in the sport.

It’s the classic conundrum of the quantified self. I know too much. And this information about time, times, gives the illusion of power and control, while the seconds just keep ticking.

So, after fifteen years of wearing a watch, I did the obvious thing, which, for a decade and a half, was far from obvious: I took my watch off.

At first I felt naked. I checked my wrist for the time constantly. When I went for runs without the watch, my right hand would automatically drift over to the start and stop button and find only my skin. I didn’t know how fast I was running, nor could I upload the data to Strava. I was in the dark, but I was also unencumbered by the anxiety of knowing more than was helpful.

Around the time of taking the watch off, I started to think of myself as retired from competitive running. Since I’d taken a long break from the sport at the beginning of 2021, I always thought I would return in a serious way. But for a variety of reasons, one being my desire to live my life without the constant pressure of high level training and performance, I have not returned to competitive running.

What I’ve done instead for the last several years, is slog through weeks of minimal “training” in an attempt to maintain some level of base fitness so that when I might choose to run seriously again, I wouldn’t have to start from scratch. I didn’t want to bury my running future, but I didn’t want to get up at 6am every morning to work my tail off. I didn’t want to lose my running identity or my watch tan, proof of who I was and who’d I’d been, but I also didn’t want to wear the watch anymore.

My extremely corny current therapist asked me what it would feel like if I could look into a crystal ball and see that ten years from now, I hadn’t accomplished, and wouldn’t accomplish, my Big Running Goals. “What would that change for you now?” she asked.

It’s a painful, grief-laden thought, but a liberating one. It would relieve me of any pressure to train now, or ever. It would let me off the hook of feeling like I should be using my best remaining running years to train as hard as possible. It would let me retire without having to pretend I might still come back to the sport later.

Months ago, someone I’ve been seeing referred jokingly to my “exercise watch.” I felt suddenly silly, aware of the Garmin’s large profile and said, “I can take it off.”

“No!” she said immediately, “It’s part of you.” But it isn’t.

Slowly, I’ve been letting my watch tan fill in. Lying in the sun on my roof, floating down the Russian River, playing soccer with my roommates, my wrist bare. Going to a party, hanging out late, with no idea what time it is, and thinking “I guess I’ll just go home when I feel ready to go.”

The edges of the watch tan are faded now, though there’s still a faint band of pale skin on my left wrist. It’s almost imperceptible in a photo. But if you squint hard, you can just barely make it out.

I too have a watch tan. Mine is from working outside, and like you is set to a clock (our station’s time clock in my case). My wife hates it, my kids find it hilarious, and my younger coworkers can’t believe I don’t just use a phone like everyone else... they also ask me how much longer we have until our next flight lands, ‘cause we’re not allowed to use our phones out on the flight line. Go figure.

For me, it represents time on a longer scale; it’s not about timing runs (spoiler alert: you can likely walk faster than I jog), but rather the passing of seasons. Every time it shows back up means another winter has passed, and another summer is here.

I found it fascinating to think about how controlled we are by all our devices if we allow it. Great food for thought. I used to worry about making the three goals on my watch (move, exercise, stand) and just decided to be grateful when I hit all three, but not to think about it otherwise.