I wrote this essay for a class last semester and never figured out exactly what I wanted to do with it. I feel increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of publishing personal essays on the internet outside of Substack (will probably address those feelings in a post at some point…), so this felt like the right place for it. :)

Eight women lined up on the curved start line of UC Berkeley’s crumbling outdoor track. They stepped into ready positions, bodies taut and flexed in the stretching seconds before the gun sounded. Bang!

They sprinted off the line, then settled into a rhythm of footsteps. In seconds, they approached the first barrier—a hulking obstacle that stretched across three lanes of the track. Unlike its lighter, more forgiving cousin, the hurdle, a steeplechase barrier does not move when you hit it. It’s sturdy enough to knock you down.

One at a time, they leapt over the barrier, each runner’s head bobbing up into the air before her feet met solid ground and she resumed her steady steps.

Steeplechase is the most grueling event on the track. Before people ever ran the race, horses did. They soared over logs and streams, hooves beating the earth as they ran between church steeples in rural Ireland. According to the World Athletics Association, men ran the first steeplechase at Oxford University in the mid-19th century. The race was not designed for bipeds, yet we force our bodies through it anyway.

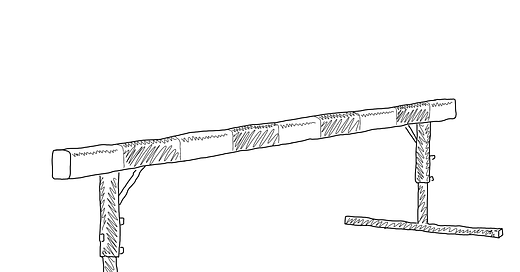

Over the course of three kilometers—that’s the standard distance in college and the Olympics, just under two miles—human steeplechasers hurdle 35 barriers. Most of these are positioned around the track on flat ground. But once every lap, for seven laps, the runners hurdle a water jump: a steeple barrier, a long black and white crossbeam supported by metal legs, similar to a balance beam, is positioned before a sloped pit, a wedge carved out from the track and filled with water from a hose, like a kiddie pool.

At the Berkeley track, I stood on the curve by the water jump. A familiar tightness bloomed in my throat as I watched the runners approach the water pit, which was shimmering with California sun. Some of the runners accelerated into the jump, building as much momentum as possible. They planted one foot on the steeple barrier and pushed off the front of it, launching themselves forward and landing in the water pit’s shallow upslope. Others ran stutter steps—their strides shortened as they approached the barrier. They plunged into the pit with both feet, coming to a full stop in the water, which stole their momentum and slowed them as their competitors charged ahead.

Suddenly, I was acutely aware of my ankles.

When I practiced my very first water jump in college, I thrust myself off the barrier with one foot, planted hard in the pit with the other, and fell forward, sprawling face first in a splash, skinning both knees and spraining my ankle. The steeplechase is unforgiving.

But that’s why I loved it. It made me feel strong, gritty, brazen. It made me feel reckless, when I was often overly cautious. Once I ran a race in Virginia and found myself in midair over the water pit as someone fell in front of me. I twisted my body mid-leap and found a clear place to land, so as not to spike the body of the fallen runner shielding herself with her hands.

Sometimes, I went down. I remember approaching one jump, sure I had clearance, but, more exhausted than I realized, I clipped my rear leg on the barrier. In a comically slow tumble, my body hit the track. I lay there for a dazed second, confused by how I’d gotten there, then bounced up and finished the race.

My falls and resulting injuries were all minor, but I knew the stakes. In practice, I’d seen a teammate try a jump, hit the hurdle, and crumple. He lay there, his leg bent in a way it shouldn’t. The indoor stadium, which had just been buzzing with our chattering voices, went silent. We found out later he’d shattered his femur, the strongest bone in the human body.

In my senior year, my mom traveled from Indiana to Connecticut to watch me steeple. She’d never seen me race over barriers before, and she stood on the backstretch, unable to draw herself toward the water pit in all its chaos and potential for disaster. Afterward, she confided that it was the only time she’d ever been scared to watch me race.

I started steepling almost out of spite. I had been a college track team walk-on and was never quite fast enough to compete with the best middle distance runners. My training partner nicknamed us “the last of the fast;” we squeaked into the invitational meets, but we were never in contention to win our races. I was tired of barely holding onto a pack of runners who could outkick me. I was tired of monotonous flat laps around the track. I was tired.

I told my coach I wanted to try steepling, and I got a “we’ll see.” But I kept asking until she relented.

I thought I knew what I was getting into. I had been running competitively for more than eight years at that point. I knew what it felt like to be tired, to push through exhaustion and find one more gear. But I did not know what it felt like to steeplechase. Lifting your body into the air 35 times while running as fast as possible saps energy like a leak in a gas tank. Fuel burns far faster than what you budget for.

My first steeplechase was an early spring race on Harvard’s outdoor track. A gusty wind rippled the American flag and whipped against my face. I made it through a third of the race before I wanted to drop out. Every cell in my body was tired. My legs were tired my arms were tired my jaw was tired my teeth were tired my hair was tired. I calculated that I had 20 barriers left. I had to will myself into the air 20 more times.

I saw this would not be possible. Forward motion was no longer my choice. Instead, the track suddenly appeared to me as a video game, each barrier materializing and advancing upon me, and I had to leap over it. One hurdle: 19 left. Then 10. Then 5. I jumped until there were no more, just one final stretch of sublime, flat ground, and I crossed the finish line, my shoes drenched in water from the pit, my body drained. I stood panting, breathless with exhaustion and exhilaration.

In my obstacle-less running career of flat track and cross country, I had spent many frustrating years working my tail off just to shave a few seconds off my times. But the steeplechase was an opportunity for massive improvement. Every race I ran, I ran faster. I learned how to skim my lead leg over each barrier to conserve energy. I practiced the water jump relentlessly and learned how to cycle my legs in the air, how to land with one foot wet, one foot dry, ready to charge out of the pit. I stopped counting how many barriers remained and focused only on the obstacle before me. I taped my ankles for better support. I peeled off my socks so they wouldn’t absorb water inside my shoes and squelch with each step.

My best steeplechase in college was my last. Every jump felt smooth, effortless. I tucked myself in behind the woman leading the race and relaxed into her pace. With a couple laps to go, I pulled ahead, decisively, and I knew she was not coming back.

I was the most powerful version of myself. I was a steeplechase horse. Muscles pulsing. Mouth foaming. I galloped over the barriers with no rider, no bit, no saddle. I tasted animal instincts on my tongue; this was how my body was supposed to move. I ran and I jumped and I ran.

Later that night, I went drinking with friends. I knocked back one beer after another and kept saying, in progressively incomprehensible speech, “I’m retired from running!” At first, I laughed, excited by a newfound freedom from discipline. I accounted for what I’d given up in the name of running: late nights and lazy mornings, weekend adventures and spontaneous exploration, endless kegs and fried food, concerts and parties that required too much standing, the opportunity to be anyone else. Being a runner meant saying no, so that when I stepped up to the line, I could instead say, “I have done everything I can to prepare.” Now, I had nothing to prepare for, and I grew devastated by that understanding, repeating it in my stupor. I ended the night weeping with my cheek pressed to the toilet seat.

In fact, I wasn’t retired from running. I continued competing for two more years, but I never ran another steeplechase. I offered explanations to myself: It required too much technical work. I didn’t have anyone to train with. I needed equipment I no longer had access to. It was too damn hard.

But I thought I’d lost what defined me. The toughest parts of myself, the feral, instinctual, ruthless, animal parts of myself, they would all atrophy if I didn’t exercise them. I had spent years training for performance: hurdle drills in the dark after everyone else had gone home, early bedtimes, grueling workouts, strength training, wet feet and sprained ankles and scarred knees in service of running fast, in service of being exceptional. I thought my body only as valuable as what it could do. A racehorse that doesn’t race is just livestock.

Five years later, I stood on the edge of the golden track and watched the steeplechasers clear the last water jump. The race, which had started with eight competitors, was down to six. The lead woman hoisted her body over the barrier and trudged through the pit in bedraggled form. Her coach jogged by and shouted, “She’s gonna break 11 minutes!” Then the five stragglers cleared the barrier, their braids and buns and hair ribbons bouncing in the air as they mustered the energy for one last leap.

They flew down the straightaway. Through the finish line. Then dispersed to put on a dry pair of shoes and slide back into their lives. I stood for a few minutes, scanning for the racers who had just finished, wanting them to know that I understood, that I was one of them. But they were gone.

A few days later, I clabbered up a long staircase and ran over packed dirt paths that wove through an explosion of poppies in the Berkeley Hills. I crested a rise that overlooked the open, glittering Bay and the San Francisco skyline. Then the trail twisted into the shade of tree cover, and 50 meters in front of me, a massive trunk blocked the path, downed by recent storms. I kept my eyes trained on the obstacle, and everything in me that had felt loose and tired and out of practice felt sharp and familiar, there all along. I accelerated as I approached the tree, then stepped on the bark and pushed off into the air. For a second, I was flying—legs outstretched, buoyed by a cushion of air—and then I felt the tug of gravity, and my feet met the ground.

Gorgeous writing ♥️