This is the last newsletter of 2021. I intended to send it out last Friday as usual, but I found myself in Indiana working on an impossible puzzle of Botticelli’s La Primavera instead of writing, so here we are, sending this out on a Monday (thanks for your flexibility).

At the end of this newsletter, I’ll ask you to take a 1 minute survey so I can make the newsletter better next year.

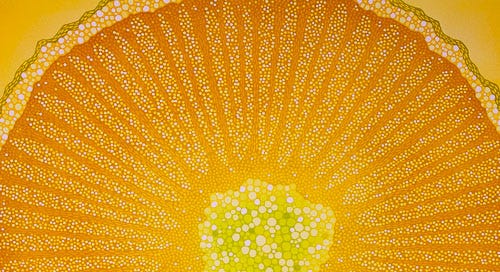

My mom has an artist friend, a printmaker, whose work appears throughout our house. She draws most of her inspiration from the natural world: leaf veins snake through a frame in our living room; the cross-section of something celled and citrusy blooms in our kitchen.

Some of her other work gestures toward ripples, clouds, an aerial view of Midwestern farmland, a wandering river in gold leaf. Each piece of work is as alive as the natural world it captures. Her art bends, reflects, unfurls. Motion is arrested within the frame. Life, suspended.

Over last night’s Swedish meatballs, we started talking about her art. “She’s been making art for 30 years now,” my mom explained of her expansive, still expanding portfolio. She has far more art than what is selling (what to do with decades of work that was fresh and exciting when we created it, and less so when we have years of creative growth between then and now?). I imagined the artist in her basement studio, laboriously carving into linocut blocks as exquisite, unsold pieces piled up around her. Covid has not canceled art, but it has certainly canceled art shows.

“She has so many prints that she’s burying them under her mulch,” my mom continued, “It keeps the weeds down.”

I felt my body tighten. “She’s burying the prints? Under dirt?” I asked desperately, and my mom nodded in confirmation.

From the earth her work came, and to the earth it returns. She borrows from the natural world, sourcing and gathering inspiration out of doors, and I tried to find a palmful of poetic resolution in the fact that her art helps her garden flourish. But, no one will look at the art beneath their feet. The canvas is left to the blind creatures of the soil. Once it’s buried, it has lost every admiring eye.

“Well, can’t she print more?” my dad asked as one of her prints hung behind his head. My face fell in horror; “No!” I said, too emphatically across the dinner table, “No, she can’t.”

The medium she uses, linocut, is unforgiving. She begins with one block of linoleum and carves out pieces with a sharp metal gouge. Then she rolls a layer of ink onto the block, presses it onto the paper before returning to the same block of linoleum and cutting away more and more. Again, she rolls on a new layer of ink, another color, then presses it again onto the same paper. She writes of this iterative process, “My reduction linocuts are created by a conversation between carving away layers of one linoleum block and printing the resulting pattern in overlapping inked layers, until the block is mostly carved away, or reduced.” As the print is built up, one inky layer at a time, the linoleum block is whittled away.

Once she cuts again into the same block, there will never be more prints than there were to start with. Those 20 or 5 or 2 prints are all that will ever exist. Some of those prints hang in our house, some remain filed in her studio, some return to the earth.

At the end of this long year, I find myself fixated on what has been cut away: what I am left with after months and months of Covid carving off pieces of ourselves until we feel defined by reduction. Selves in relief.

But through this paring down, something else is produced by, in, each of us. It may simply be a record of this year: inky layers of remembering. But it could be new or changed relationships. Revised or deeper understanding of ourselves. Maybe a bending direction—new life trajectory. It could be some small small act of forgiveness, for ourselves, or someone else.

My impulse, no doubt shaped by our capitalist obsession with productivity, is that whatever was created must be displayed or published, showcased and shared with the world. I have written a lot this year, but my most important work was healing myself. It’s a product that can’t be framed or sold. I can’t even name it as productive or valuable under the rules of our society.

Best to return it to the earth. I know it’s there, I know it matters. Even in the dark.

If you are interested in viewing (or purchasing!) Elizabeth Busey’s work, you can look through her stunning portfolio here.

A small ask

If you have a minute, maybe you’ll consider taking this survey so I can make the next year’s newsletter better. I’ll see you in January.

"I know it’s there, I know it matters. Even in the dark."

Probably not a coincidence that you focused on reducing productivity and returning to the earth around the time of the winter solstice. Winter is a time for slowing down, going inward, even going under-ground, into the earth, for warmth, just like some hibernating animals do.